“God created war so that Americans would learn geography” – Mark Twain

I was once asked to sing some of Phil’s songs at a Peace Festival in Liverpool organised by CND. I immediately said “no”, then thought about it and eventually said “yes”, unable to resist the opportunity to sing Phil’s songs to an unsuspecting public, no matter how nerve-wracking it may have been.

Standing in the shadows of the ruins of a church gutted by Nazi bombs, strumming nervously, one moment stands out. Standing there is 2010, singing a 45 year old song I got to the words;

“We spit through the streets of the cities we wreck,

We’ll find you a leader that you can’t elect”,

I felt this surge, this rush of blood to the head. I can almost feel it now, that same feeling, somewhere between anger and excitement; anger that these words can still ring so true, excitement that Phil was able to capture so purely something that would blast down the decades.

At that point I forgot my nerves, letting the lyrics come spilling out, the current events giving new life to decades old lyrics, feeling as I sang that same righteous anger that Phil must have felt when writing them;

“We’ve done this before so why all the shock?”

*

“We…began to feel the sense of a world power, that possibly we could control the future of the world…” – Clark Clifford, Aide to President Trueman

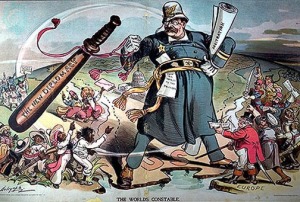

Cops Of The World was written at a time of escalating American involvement in Vietnam, from 16,000 troops in 1963 to over 180,000 in 1965.

This isn’t just about Vietnam however. Writing at a time when the so-called Islamic State are goading the west with their particular brand of unimaginable horror it is important to consider the wider role that American military intervention has played in destabilising the peace of the world.

It’s about Korea. China. Cuba. Guatemala. Indonesia. Congo. Peru.

Later Phil could have written about Laos. Cambodia. Grenada. Libya. El Salvador. Nicaragua. Panama. Iraq. Sudan. Afghanistan.

The difficulty is that anti-American feeling (however justified some of it may be) has created an impression of American monstrousness that makes this a topic difficult to discuss with any kind of a clear head.

The joy of Phil and his brand of unsentimental songwriting allows the listener (in my case, the uneducated listener) the opportunity to step back from the bigger picture with all the pitfalls of various biases and consider things from Phil’s perspective.

In dispensing with the daftness of Draft Dodger Rag nor utilising the pin point song-as-movieness of Santo Domingo, nor going for the almost abstract madness of White Boots Marching In A Yellow Land (which though released later, dates from around 1965) – Cops Of The World retains elements of all these songs.

The overall feeling, besides the obvious anger, is perhaps disappointment. Key to an understanding of Phil’s approach to the topic of American military intervention is that, at this time at least, Phil was still something of a patriot. And this is the problem! Phil wanted to believe that there was inherent good in America, that the good he felt he could do – through his songs and his activism – was inspired as much by his nationality as his politics. His good was an American good. And yet there was an ever growing list of evidence to suggest otherwise – both at home and abroad.

Images of patriotism and American culture litter Cops Of The World, “our Coca Cola is fine, boys”, “have a stick of our gum” (a line echoed in Santo Domingo “the soldiers make a bid giving candy to the kids”), “if you like you can use your flag”, “we own half the world, oh say can you see” – distorted images of distorted motives. For that is the key to an understanding of this very American brand of militarism – the awkwardness of knowing that while there is good there, deep down, well-hidden – the real motives for these actions are not moral but ideological and economic. This isn’t so much empire-building, as market-building – “the name for our profits is democracy”.

And there it is, that most unholy of motives. Money. What was that Billy Bragg lyric? “War, what is it good for? It’s good for business”. There’s more to it than that. Somewhere between machoness and childishness – “We’ve got too much money and we’re looking for toys, guns will be guns and boys will be boys” before the killer (literally) line –

“And we’ll gladly pay for all we destroy”.

(This last line brings to mind Arthur Clough’s epic satirical poem Dipsychus which he began writing in 1850 –

I drive through the streets, and I care not a damn;

The people they stare, and they ask who I am;

And if I should chance to run over a cad,

I can pay for the damage if ever so bad.

So pleasant it is to have money, heigh ho!

So pleasant it is to have money.)

A nation obsessed with money, obsessed with its power. Money as kingmaker and serf destroyer. Money bestows the ability with such totality, that motive and conscience follow tremulously in its wake.

Remember though that the refrain, repeated not once but twice at the end of each verse is “We’re the cops of the world, boys”*. “We’re”. This isn’t that modern sport of America-bashing from without. This is America-bashing from within; an American singer singing to an American audience. The key here is complicity.

Cops Of The World is Phil’s ode to refusal.

*

It would take a couple more years to Dr King to acknowledge it, but the links between the civil rights and peace movements were becoming undeniable. In What Are You Fighting For? Phil sang “if we win the wars at home there’ll be no fighting anymore” – a line that I have always found slightly uncomfortable, but the inference is clear – that internal injustices were being echoed externally.

As with the images of patriotism, this song is also filled with images of bigotry, be it anti-Communist (“dump the reds in a pile, boys”), misogynist (“just take off your clothes and lie down on your back”) or racist (“we don’t care if you’re yellow or black”).

In Dr King’s great speech denouncing American involvement in Vietnam he addressed the issue of whether he, as a civil rights leader, should involve himself in the peace movement;

“In 1957 when a group of us formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, we chose as our motto: ‘To save the soul of America.’ We were convinced that we could not limit our vision to certain rights for black people, but instead affirmed the conviction that America would never be free or saved from itself until the descendants of its slaves were loosed completely from the shackles they still wear…

“Now, it should be incandescently clear that no one who has any concern for the integrity and life of America today can ignore the present war. If America’s soul becomes totally poisoned, part of the autopsy must read: Vietnam. It can never be saved so long as it destroys the deepest hopes of men the world over.”

Beautiful. A little late perhaps, but beautiful all the same.

So the next time someone uses its various military incursions to denounce the good name of the United States of America remind them of Dr King, of all those Americans who fought for peace and continue to fight for peace.

And remind them of Phil Ochs – American.

*An end note about an odd note. At the end of each verse Phil plays a mischord. A moment of inspired disharmony. I’m assuming this is on purpose! It’s uncomfortable, a little moment of the kind of experimental excesses we’ll later hear on Half A Century High and The Crucifixion.